Picturesque Stourhead – Steve Middlehurst 2017

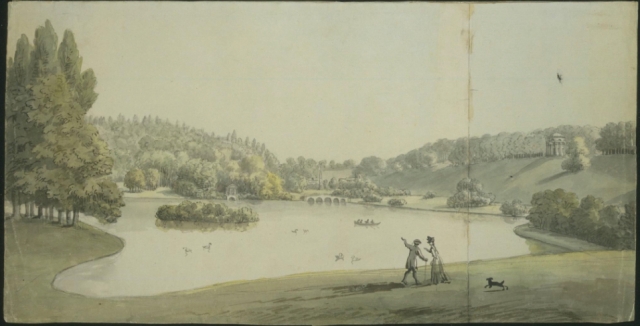

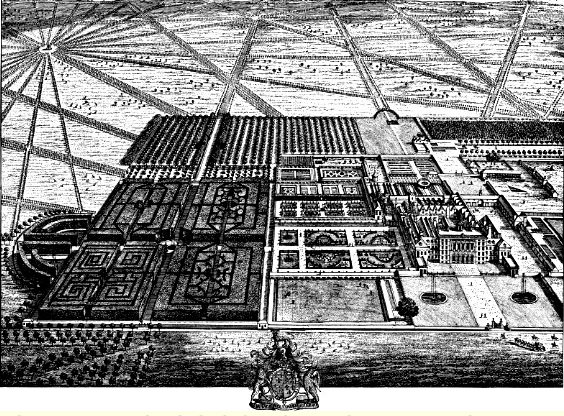

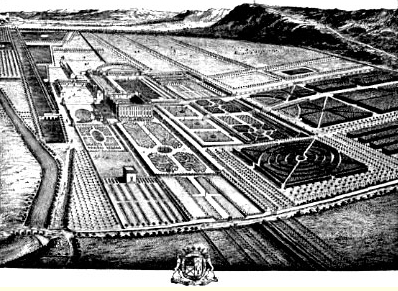

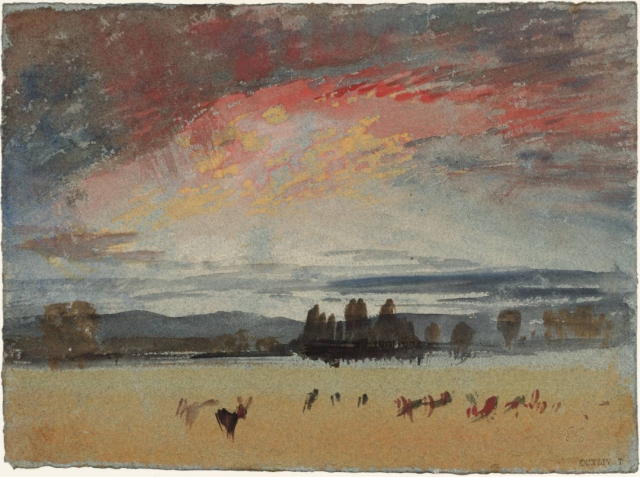

Landscape photography is a broad church and when compared with the other main genres of photography it is perhaps the one that comes with the most historical baggage. I have discussed at some length its roots in landscape painting (here) but beyond that historic context the conventions of painting in terms of subject matter: the picturesque, pastural, grandeur and sublimity to name but a few, and in terms of composition continue to dominate contemporary, popular landscape photography.

Following an approach promoted by most of the photographic press, how-to books, photography clubs and websites many photographers have perfected the representation of a perfectly lit, picturesque view of pastural, coastal or wild Britain. I admire the results, recognise their technical expertise, respect their dedication and admit, particularly in my medium format days, to searching out the reflection of mountains in dark lakes, autumn colours on misty mornings and idyllic rural scenes. In terms of aesthetics there is little wrong with the best of such work, the picturesque is popular because most of us take pleasure from beautiful scenery but it is often more pop than jazz, alluring, technically perfect and formally composed; however, only the most exceptional piece passes the test of time, whereas jazz offers multiple levels of complexity that draws us back time and again to explore it more deeply.

There are two main problems with popular, picturesque landscape photography; firstly the pictures are often presented as single images or collections linked only by broad geographical categories as opposed to series that develop conceptual themes. This reduces the images to scenic snapshots that concentrate attention on the visible, superficial characteristics of the land; the eye-catching reflections disguise the dark waters of the lake, the striking autumn colours camouflage the forest.

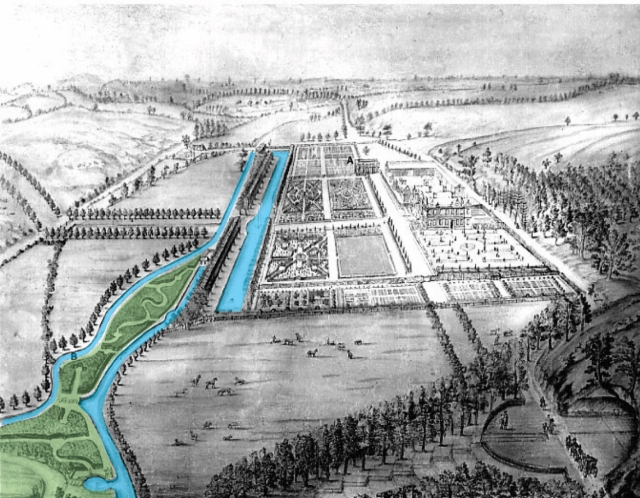

The second problem is that the search for an ideal viewpoint and perfect light tends to idealise the land, promoting a rural idyll that advertises rather than investigates the countryside. The nature of the advertisement may, as previously discussed (here), have some similarity to the early photographers of the American West by presenting the landscape as real estate, a place to invest, exploit or settle. Alternatively, and harking back to the picturesque painters of the eighteenth century or Ansel Adams in the American National Parks, it can promote the land as a tourist amenity, a place to visit, a view to find or even, in the age of social media, to capture as a trophy photograph.

In either case the end result is to compress a million years of geological transition and twelve millennium of human intervention into, what Liz Wells calls, the “welcoming picturesque” (1: p.164)

Jem Southam – The Red River

The Red River, Reskadinnick – Jem Southam 1982-1989

Jem Southam’s landscape series are jazz; complex, challenging and initially a little bewildering; photographs that demand we return to investigate multiple layers of complexity and to decode his intentions. Few of his photographs are scenic in any picturesque sense; he frequently studies discrete spaces isolated from the wider countryside with tight compositions, misty backgrounds or flat horizons under white skies. He rarely attempts to portray a place in its entirety; his perspective of the land is contained in series of economically framed viewpoints that represent the landscape as a mosaic of details through which its history, present and future is revealed. This sensitivity to history is best seen in the Red River (2) Series in which he explores a Cornish valley formed by a geographically insignificant brook finding the shortest route from the Bolenowe Moors to the sea at St Ives Bay. In their essay that contextualises the photographs Frank Turk and Jan Ruhrmund describe the history of the valley and its river from the ice age to human habitation and agriculture, to the development of small-scale tin and lead processing, its nineteenth century decline and finally the post industrial age. (i) (3)

This background history is fundamental to understanding Southam’s photographs which chart the complete cycle of the valley’s geological origins, the rise and demise of the primordial forest, its long period as a pastoral idyll, the ravaging of the land by mining and industrial processes through to industrial decline and the area’s subsequent reinvention as a recreational amenity. The sweeping scale of this series is breathtaking, few photographers have attempted to record such a monumental passage of time and all in less than fifty photographs.

Bolenowe – Jem Southam 1982-1989

The passage of time is matched by the diversity of the pictures. He uses natural rock formations and old farm buildings to describe the black rock at the source of the valley; wooded valleys, and detailed studies of lichen loaded branches to represent the primordial – a hint of what is to come in his much later The River Winter series. For pastoral idyll he offers a careful judged mixture of broad landscape and telling details, contrasting the lush pastures of Bolenowe with the grey stone farms that speak of hard places, marooned amid brooding hills and muddy yards that starkly contrast the image of Cornwalls’ rivera with its quaint fishing villages and boutique hotels.

Mine Engine House, the Great Flat Lode, Newton Moor. – Jem Southam 1982-1989

The sequencing of the series takes us from the sublime high moors, into the dark forest, cleared to create the wide open spaces of farming that were then invaded by the santanic mills of industry and below the surface into Tolkien-like tunnels carved through the rich red rock in search of minerals. Following the trajectory of the locations our emotions move ever downwards before he lifts the mood with new farms, bright gardens and tourist beaches. Few photographers master the art of narrative, the medium mitigates against easy story telling; Red River is a sophisticated, complex but ultimately successful narrative because it demands our close attention; asking us to recognise the rhythms created by his changes in perspective, from close shot to broad vistas and his use of colour to juxtapose old with new, nature with industrial debris and life with death.

Southam describes his approach:

“I ensue grandeur for the sake of it, preferring to revel in a subtler scale and history. But there is still an epic story to be told, which exists wherever humans have made their homes.” (4)

There is a honest reality about the Red River, it is not the Cornwall of postcards, Doc Martin and yellow, cream-rich, ice cream. It is initially melancholy, history weighs heavily on the first two thirds of the series; a deforested landscape, failed industry, struggling farms, dilapidated buildings and a land scarred by man’s exploitation but towards the end it contains a strong narrative of rebirth and reinvention. In a series that excludes any human subjects we find the story of man’s interaction with the land and a community that has consistently found new ways to survive in this valley.

??

The River Winter

The River Winter (5), created some twenty years after The Red River, develops many of the same themes but by comparing the two series we can map the development, or perhaps it is better described as the refinement, of Southam’s voice. Andrew Nadolski highlights the way this series draws “on an almost medieval notion of the dark, deep winter.” (6) By studying a small river and a local landscape that both defines and responds to the river’s moods and movements, Southam asks how we see the countryside, what is a river and what is winter. The long term decrease in agricultural and land-based work, the shift to first industrial and then commercial employment and the resultant ruralisation of the population has isolated twenty-first century man from the natural world. Seasonal shifts in weather patterns are considered in terms of their impact on our movement in air conditioned transport between centrally heated homes and climate controlled commercial premises; once inside these artificial spaces we are cocooned from the direct impact of the weather. Few of us will visit the dark, damp, cold, grey and denuded winter landscape of a rural valley, preferring the warmth of towns and cities, the drama of snowy mountains or wild coastal vistas; if we visit the countryside at all in winter we continue to seek out the sublime or the picturesque and ignore the detail of a dormant land.

Leat, River Culm at Rewe, 6 December 2010 – Jem Southam 2010

To our distant ancestors the impact of winter was directly life threatening; the shortening of days, falling temperatures, rising rivers, flooded lowlands and the need to slaughter livestock for lack of grazing and the labour of storing food for the dark months were the precursor to their most challenging period of the year. It is no coincidence that mid-winter has been the most important festival in northern climes since pre-history; sun rise at the winter solstice symbolises the return of life to the land. As Southam points out:

“Winter is embedded in the imagination and culture of those of us who have lived our lives across North Western Europe.” (6)

As well as evoking the cultural memory of winter he also mines the myth of the forest, a subject he previously explored in The Painter’s Pool. These two themes combine in an evocative way so that the dark waters of the Exe and its tributaries running beneath winter trees taps into our fear of cold icy water and dark living forests, places of mythical creatures and dark deeds.

The Red River was organised as a chronology of many millennium, a sweeping historical view; The River Winter remains chronologically organised, it follows a single winter, but despite this comparatively brief timescale Southam continues to draw the history of this and any similar place into the pictures. There is a sense of timelessness, of the season’s cyclical changes being painted onto a canvas of an ancient river in an enduring landscape; it is the winter of 2010/11 and every previous winter seen on this river.

The other overriding sense we gain from the series is that of a diary; a walk through the season, a re-animation of Southam’s progress along the banks of the Exe and its tributaries that winter. Hotshot Magazine describes his work as belonging “to a British tradition of close-looking and thoughtful study and reflection” (7) and this translates into the series being a very personal viewpoint bringing Southam into the pictures and underlining the sense of following in the photographer’s footsteps.

The Painter’s Pool, 9 November 2003 – Jem Southam 2003

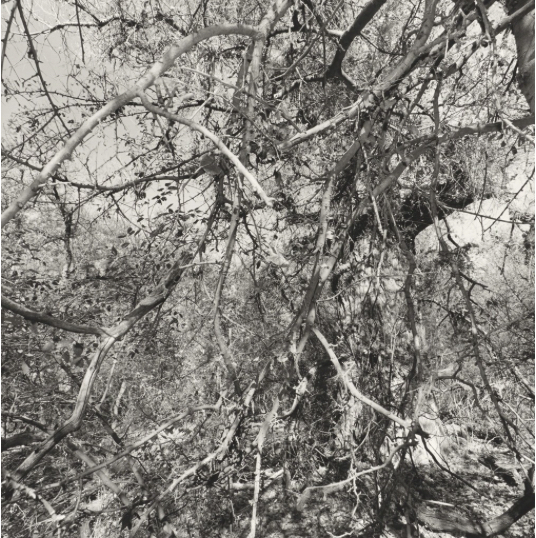

If we view River Winter in the context of Southam’s wider body of work we can identify other themes; in Painter’s Pool he investigated the challenge of a colleague who was painting woodland scenes from vantage points under and surrounded by the canopy, he described this idea in an interview with Andrew Nadolski:

“How does someone who draws or paints deal with the extraordinary visual complexities presented when standing in the canopy of a wood?” (6)

The published series is not unique, Lee Friedlander recently published interpretation of the American West includes similar but monochrome studies (8), but the sheer complexity of many of the pictures refused the idea that the photographer’s role is to simplify complexity. In Painter’s Pool he represents the cycle of birth and decay; the balance between man’s intervention and neglect and of the visual diversity of tiny areas of wilderness that have survived or fought back against the deforestation of the land.

River Exe at Bickleigh, 22 November 2010 – Jem Southam 2010

In River Winter he returns to these same visual complexities but now the river is ever present in the background, slowly but remorselessly wending its way seaward behind the tangle of branches, twigs and dying or dead leaves. The resultant work is more topographical than Painter’s Pool, the river and the broader landscape offers more context to the forest but he continues to bring to our attention that it is in winter that the countryside is stripped bare and behind living nature and along side the ever moving river there is always stillness, death and decay.

Everything about Southam’s work is contemplative, there is a stillness in his compositions that reflects the slow process of 10 x 8 photography and the premeditation of the photographer. In Italy there is a slow food movement that grew in response to the spread of American-style fast food outlets; towns and cities attempt to block what they see as a cultural invasion by burger bars and thick crust pizza stalls; Jem Southam promotes a slow photography movement, an alternative to the rapid, thoughtless and excessive capture of thoughtless images that digital photography has facilitated. He takes forty to fifty pictures a year (6) so the forty photographs in River Winter represent a full year’s output not an edited down selection of thousands of negatives; I find this idea humbling.

River Culm at Silverton Mill, 22 January 2011 – Jem Southam 2011

As previously argued Southam’s work has multiple layers of complexity beneath the obvious visual surface of the prints; he is deeply interested in the land in the context of its history and our relationship to it. We recognise that all the land on our small islands has been modified by man to provide habitats, food, the site of industrial processes, the raw materials of technology or as transport routes and we like to think of this in terms of planned and structured processes; deforestation for agriculture and ship building, the industrial and agricultural revolutions, the growth and decline of the railways, the creation of the M4 high-tech corridor or the trading hub that is the City of London but these events are only logical and structured when viewed in hindsight. Southam seeks out the unstructured, chaotic corners of the land that hold the evidence of man’s casual intervention or “the result of the technologies required to do the particular actions required” (6)

We are very ready to describe photographers as inspirational without always being specific about what they inspired us to do. Southam taught me to look the other way, to ignore the obvious in the landscape that adds nothing to our overall knowledge of the land and to seek out the forgotten and ignored: the unintentional wildernesses we have created at major road junctions or on the verges of motorways and railways, the fringes of ancient forest that survive close to urbanisation or the land unintentionally preserved in an ancient state by the Ministry of Defence’s requisition of great swathes of Dorset, Wilshire and Norfolk for military training.

I will end with another quotation from Southam that goes some way to explaining his intent:

“My overall artistic intentions are to make work that explores how our history, our memory, and our systems of knowledge combine to influence our responses to the places we inhabit, visit, create, and dream of.” (4)

River Creedy at Sweetham, 4 December 2010 – Jem Southam 2010

Notes on Text

(i) For thousands of years after the end of the ice age man left few traces of their presence in this valley, a neolithic axe head found by a hedger, two Bronze Age barrows and a Roman style villa, and evidence of medieval wool processing show this land was hunted then farmed for five thousand years but it remained a rural backwater until the fifteenth century when an entrepreneurial family established a business mining tin and extracting lead around the Red River. In the centuries that followed these small-scale industrial processes reshaped the landscape until the “great trade recession” hit the county in the mid-nineteenth century, a national event that led to mass emigration and the industrial decline of the valley. (3)

Sources

Books

(1) Wells, Liz (2011) Land Matters: landscape Photography, Culture and Identity (Kindle Edition). London: I.B.Taurus

(2) Southam, Jem (1989) The Red River. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications

(3) Turk, Frank and Ruhrmund Jan (1989) Red River Valley (an essay in The Red River). Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications

(5) Southam, Jem (2012) The River Winter. London: MACK

(8) Friedlander, Lee (2016) Western Landscapes. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery.

Internet

(4) Schuman, Aaron (2005) Landscape Stories: An Interview with Jem Southam (accessed at Seesaw 21.2.17) – http://seesawmagazine.com/southam_pages/southam_interview.html

(6) Nadolski, Andrew (2013) Stories from the Land: Jem Southam in Conversation with Andrew Nadolski (accessed at On Landscape 21.2.17) – https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2013/03/jem-southam-interview/

(7) Hotshoe (2013) Jem Southam: The River Winter Reviewed (accessed at Hotshot 21.2.17) – http://www.hotshoeinternational.com/issues/182/books/jem-southam-the-river-winter-reviewed

Gibbons, Nikki (2013) Interview with Jem Southam (accessed at Nikki Gibbons Photography 21.2.17) – http://nikkigibbonsphotography.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/interview-with-jem-southam.html